General Sessions Court judges from across the state recently gathered for a conference in Murfreesboro where they discussed issues related to the opioid epidemic, the effects of vicarious trauma, updates to case law, and more.

In his opening remarks on the first morning of the conference, Tennessee Supreme Court Chief Justice Jeff Bivins emphasized the unique and indispensable role that General Sessions judges play in the state.

“You folks are the ones who on a day-to-day basis have more of an impact on the lives of Tennesseans than any of us do on the appellate courts or elsewhere,” Chief Justice Bivins said. “Thank you so much for that. We very much appreciate all that you do.”

The topics covered at the conference largely dealt with challenges that General Sessions judges face on a routine basis in their courtrooms.

One the most serious challenges arises from the ongoing opioid-driven addiction crisis, which was the subject of a session led by Jill Carney, a regional overdose prevention specialist with the Memphis Area Prevention Coalition. As Carney pointed out, a record 1,776 people died of drug overdoses in Tennessee in 2017. Of those overdose deaths, 1,268 were opioid-related, a grim sign of the increasing availability of dangerous drugs like heroin and fentanyl.

Thankfully, a powerful drug, Naloxone, better known by its brand name of Narcan, exists to counteract opioid overdoses. Narcan works by binding to opioid receptors in the brain, effectively blocking opioids from doing the same. Once Narcan begins working, which takes one to three minutes, the effects of the overdose are reversed. Carney trains people, including law enforcement officials and addicts, to administer the drug, which can be purchased at a retail pharmacy. She gave the judges explicit directions on administering the medication.

Carney said there have been two cases in Judge Tim Dwyer’s Shelby County Drug Court where Narcan was used to stop an overdose. She advised the judges to be on the lookout for common signs of opioid overdose, including blue lips and fingernails, pinpoint pupils, and the “heroin nod,” where users’ heads may bob up and down as they gradually slip into unconsciousness.

Carney’s devotion to her job is partly born out of personal experience. Carney, a former nurse, is a recovering addict herself; an alcoholic who progressed to prescription opioid abuse and, briefly, heroin.

Eventually, though, Carney hit bottom and began her journey out of addiction. She is dedicated now to helping others start similar journeys.

“The good part is there is recovery, there is hope,” she said. “All we can try to do is treat them as suffering addicts, and not criminals. Most of them are not criminals; they are just really sick people.”

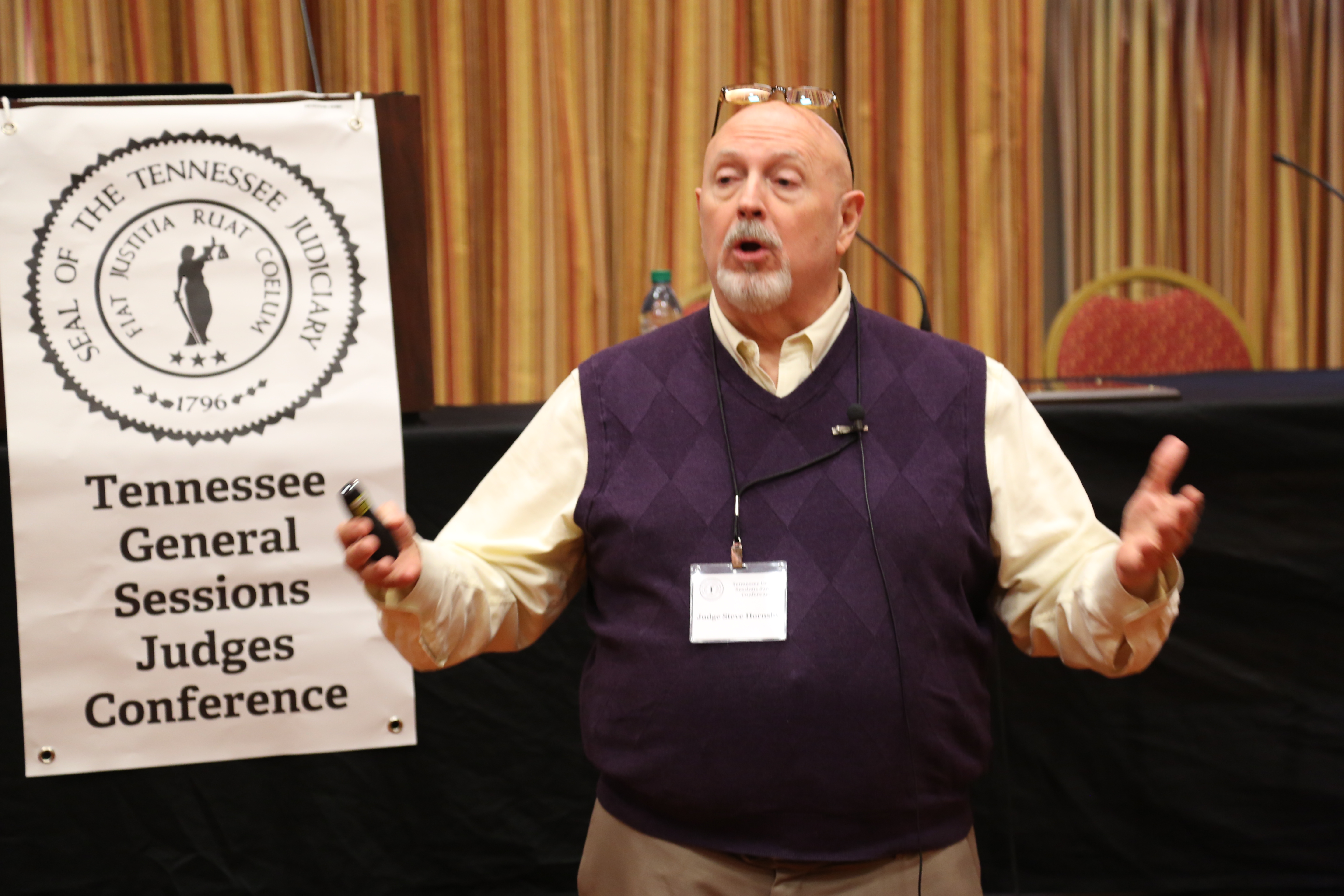

Of course, many General Sessions and Juvenile Court judges deal with the fallout from addiction every day in their courtrooms. They also regularly face people in their courtrooms who have been traumatized by violence, neglect, or poverty. This constant exposure to pain and hardship puts judges at risk for vicarious trauma. As former General Sessions Court Judge Steve Hornsby explained, vicarious trauma can be defined as “the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual impact on a person who is frequently exposed to other people’s trauma.”

“The effects of vicarious trauma are quite serious,” Judge Hornsby said. “There is now about 30 years of research supporting that vicarious trauma is something real. It’s not an imagined condition or something that is hyperbole.”

Judge Hornsby said that the negative effects of vicarious trauma can have a gradual, subconscious onset, which makes it particularly insidious.

“It sneaks up on us not from behind, but from inside,” he said. “We don’t even know it’s happening.”

Symptoms are varied, but can include everything from heightened blood pressure and increased stress, to irritability and depression. Judge Hornsby cited statistics demonstrating that people in the legal profession are at an increased risk of developing some of these symptoms. A study of 105 judges, for instance, showed that 63 percent of them had at least one symptom related to vicarious trauma. These symptoms can be especially difficult for judges, who may feel more isolated from typical social situations and interaction due to their status and confidentiality requirements of their positions.

Rather than simply surrender to these troubling symptoms, however, Judge Hornsby named a number of steps that judges can take to fight back against the effects of vicarious trauma. These steps range from getting enough sleep to engaging in creative and recreational pursuits to exercising to taking personal retreats free from electronic devices. One of Judge Hornsby’s preferred methods is his decades-long practice of mindfulness meditation.

“It allows you to get to a place of inner quiet and inner silence,” he said, where you can simply observe troubling thoughts and anxieties, rather than get swept up in them.

“We have become so absorbed in the external world that we believe that our thoughts are really us,” Judge Hornsby explained. “They are created by part of our brain that is meant to be helpful and useful, but our thoughts are not us.”

Coming to that understanding has a calming effect, Judge Hornsby said, and can lead to an increased sense of well-being and calmness.

After Judge Hornsby’s presentation, much of the afternoon was spent reviewing recent state appellate court rulings. Near the end of the day, attention shifted to a pair of rulings handed down in 2018 by United States District Judge Aleta Trauger. Those rulings mandated that, going forward, people who could not afford to pay court fines and costs or traffic fines could not have their driver’s licenses suspended as a result.

Liz Hale, the director of legal services for the Tennessee Department of Safety & Homeland Security, answered some of the judges’ questions about what these rulings meant for the adjudication of traffic-related offenses. Hale said that the department could still suspend driver’s licenses as usual for other offenses, such as accumulating points on a driving record, getting a DUI, or failing to have insurance. Licenses can also still be suspended for failure to appear in court.

Judge Gary Starnes, president of the General Sessions Conference, also took time at the conference to honor judges who were new to the bench, had recently retired, or had recently passed away. In the new category was Wilson County General Sessions Judge Ensley Hagan. He replaced Judge John Gwin, who was recognized with a commemorative retirement plaque, as was Polk County General Sessions Judge Billy D. Baliles. Former Shelby County General Sessions Judge Russell Sugarmon passed away in February. Judge Starnes noted Judge Sugarmon’s long, illustrious record fighting for civil rights.

“Because of him, things in Memphis and statewide are different,” Judge Starnes said.