When looking back at the history of women in the Tennessee judiciary, one often overlooked name is that of the state’s first woman county judge: DeKalb County’s Kate M. Drake. Overall, Judge Drake was the second woman to serve as a judge in the state, assuming the bench in 1931, 11 years after Shelby County Juvenile Court Judge Camille Kelley. Judge Drake was appointed to the bench in October of 1931, to fill the remaining term of her husband, Judge J.E. Drake, who had served as county judge for 20 years.

An October 8, 1931 article in the Tennessean announcing her appointment, noted, “Mrs. Drake, educated in Nashville, has served as a court reporter and has studied law in Smithville for a number of years. She has been active in political affairs of the woman’s Democratic Party and has served as a delegate to the state Democratic convention.”

Not surprisingly, Judge Drake’s appointment seems to have been a matter of curiosity to many Tennesseans. Everyday court business in DeKalb County sometimes made the news in the Nashville dailies, such as an October 23, 1931 article in the Nashville Banner: “Couple Married By Woman County Judge.” The article states, “The manner in which this ceremony was performed clearly indicated the efficient attempt the new judge will make to take care of every form of duty the office imposes upon her.”

The Tennessean greeted Judge Drake’s new position with a dedicated editorial in January 1932.

“Tennessee’s first woman to hold the office of county judge has had her first trial as presiding officer of the court and impressed those who witnessed the historic session with the ease, dispatch and self-possession with which she conducted her work,” the editorial board stated.

The editorial quotes an attendee at the DeKalb County court who stated that Judge Drake “conducted the business of the court in such manner as would have ‘reflected credit upon one who had been in the office for years.’”

The unexpired term that Judge Drake was appointed to fill ended in 1932. Early that year, though, she signaled her intention to run for election to her late husband’s seat. In August she won that election, with 2,688 votes, according to the Tennessean. The newspaper ran another article shortly thereafter featuring a photo with the caption “First Woman Judge.”

“This August, Mrs. Drake followed up her first honor by being elected to the office she had been holding, showing the confidence of the county had been secured and that her work had been approved,” the story stated.

In addition to conducting the regular business of DeKalb County, Judge Drake was also deeply engaged with other judges in the state. In August of 1933, she attended a meeting at Nashville’s Noel Hotel with many of her counterparts across the state that resulted in the formation of the Tennessee County Judges Association, the state’s first such organization.

As reported by the Tennessean, Robertson County Judge Byron Johnson was elected president of “the new state organization,” while “Mrs. Kate M. Drake of Smithville, county judge of DeKalb county and the only woman county judge in Tennessee” was elected secretary-treasurer.

By all accounts, Judge Drake stayed involved with the organization through the rest of her tenure as judge. A January 1934 article in the Nashville Banner, for instance, reports on a meeting of the Association that was recently held featuring a “round-table discussion of problems faced by county judges.” “One Woman Attends,” noted the sub-headline of the story, which went on to point out that Judge Drake was one of only eight members of the statewide organization who came to the meeting.

In addition to her judicial duties, Judge Drake also stayed involved with outside organizations while on the bench. For example, she was designated as a Middle Tennessee county chairman for the Women’s Division of the National Recovery Administration, a short-lived New Deal agency, in September 1933.

The work schedule demanded by the county judge position at that time also seems to have allowed Judge Drake to take on extra professional responsibilities. In November 1933, the Nashville Banner announced that Judge Drake had been appointed as first assistant to Federal Land Title Examiner Gen. J.W. Cooper in Knoxville. She reportedly asked that she be able to start her work in this role after the January term of court. As with other stories referencing Judge Drake, the article goes on to highlight the novelty of her position.

“Judge Drake, who holds the distinction of being the only woman County Judge in Tennessee, has been remarkably successful in looking after the county’s business, handling it in such manner as to bring about improvement in several funds that go to make up the county financial system,” the article reads, making reference, too, to the additional administrative role that the county judge played in that time and place.

In February 1934, Judge Drake announced her plans to run for reelection in that August’s elections. This time, though, she would have more competition, including former state senator O.E. Underhill and W.H. Atwell, who had previously served as Smithville’s justice of the peace and city recorder. While Judge Drake’s husband had been incapacitated in the hospital prior to his death, Governor Horton had actually tapped Atwell to fill in for him. It was only after Judge J.E. Drake passed away that Governor Horton chose his widow to succeed him.

While newspaper reports consistently reflected public satisfaction with Judge Drake’s work on the bench, she was defeated by Atwell in the August 1934 election. The judicial career of Tennessee’s first woman county judge was over.

During the midst of her short, but historic, career on the bench, Judge Drake was a single parent. She had two surviving children at this point in her life. Her first child, a son, had died of diphtheria at the age of 5 in 1914.

Judge Drake’s accomplishments on the bench would go on to inspire her children and grandchildren into the present day. Indeed, at least one of her descendants credits her with inspiring her career in the law.

Katherine Vines Trumbull is Judge Drake’s granddaughter, the child of the judge’s only daughter, Josephine. She is an attorney in Connecticut who serves as associate general counsel for Webster Bank.

While Judge Drake passed away before Trumbull was born, Trumbull was always captivated by the stories she heard about her grandmother and by her personal papers, including poetry and sketchbooks, that had been passed down.

“She was someone in our family who was larger than life,” Trumbull said. “She’s the Katherine I’m named after, and who I always tried to live up to.”

Trumbulls’ mother had a lot of memories she would share about Judge Drake, many of them focused on the judge’s adventurous spirit. She grew up hearing, for instance, how Judge Drake was an ardent suffragist who loved to travel, at one point venturing up to the Chicago World’s Fair. When she decided that she would like to learn how to work a Linotype machine, she journeyed to New Orleans to take a course.

“She was an inquisitive person,” Trumbull said. “Always interested in learning and growing.”

Apparently, her independent nature was not a problem for her husband, Judge J.E. Drake, which may have been one of the secrets to their marriage.

“They must have bene a fascinating couple because he was supportive and encouraged her,” Trumbull said.

Trumbull also appreciated the feistiness that came through in some of the stories about her grandmother. In one such tale, Judge Drake, barely 5 feet tall, armed herself with a skillet and marched to a neighbor’s house to defend a friend who was being abused by her husband.

Trumbull grew up in the pre-Title IX era and does not think she would have pursued a career in the law—a career she loves and calls “wonderful”—if it had not been for the example of her grandmother.

“If she could do that then, you really could think about doing whatever you might want to in terms of careers,” she said. “She served as an inspiration and an eye-opener in that regard, which I think was just an amazing gift.”

Trumbull added that her grandmother’s influence has ended up being multi-generational. Trumbull’s daughter, Elizabeth, was also inspired to go to law school due to Judge Drake, she said.

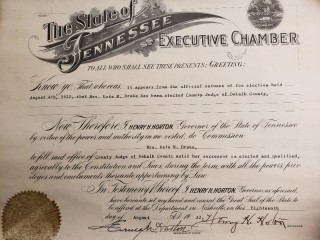

Thankfully, Trumbull still has a number of mementos to remember her grandmother by, including the original state certificates, signed by Governor Horton, that were given to Judge Drake upon her appointment and subsequent election.

After she lost the 1934 election, Judge Drake moved on to different types of work. Her next job after judge was working for the Works Progress Administration, where she was named “supervisor of women’s projects in the second district” and then the third district, according to a 1937 Chattanooga Daily Times article. At least one of the projects she helped oversee had to do with sewing. She was quoted about this project in an October 1936 Nashville Banner story: “Mrs. Kate M. Drake, Cookeville, District Two, told of one sewing project worker who said there hadn’t been a sewing machine in her family for five generations. She said some women walked ten or twelve miles to take lessons.”

During this period, she was also named the director of the Upper Middle Tennessee District of the Tennessee Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs.

In the years that followed, Judge Drake worked for a lumber company in Cookeville and then moved to Johnson City, where she was a dedicated volunteer for the American Red Cross, as evident by numerous stories in the Johnson City Press either mentioning or picturing her while engaged in Red Cross work.

Judge Drake passed away in Johnson City on January 7, 1949. The obituary mentions that members of her Sunday school class would act as flower bearers for the funeral.

Judge Drake’s historic service seems to have receded from public memory fairly quickly after her time on the bench was over, although efforts have been periodically made to keep it alive.

One such episode came in December 1937, just a little over three years after Judge Drake left the bench. In an editorial titled “County Judge Kate Drake,” the Nashville Banner editorial board admits to an error.

“In commenting editorially upon a news item from Illinois, announcing the election of Miss Jessie Summers as County Judge of Iroquois County in the state, THE BANNER a few days ago accepted a statement in the news story to the effect that she was the first woman elected to such an office in the country,” the editorial states. “The dispatch accorded her that distinction and credited it to the showing made by records of the American Bar Association.”

The Banner then went on to declare that certain readers had pointed out that this information was not correct.

“Friends of Mrs. Kate M. Drake of Smithville in this state enter ‘an objection’ to the statement that Miss Summers was ‘the first woman county judge,’” the editorial reads. “Mrs. Drake’s service in such an office in DeKalb County antedated that of Miss Summers by several years, and she served to the satisfaction of her constituents, as evidenced by her election by the people following her appointment by Governor Horton.”

The editorial next highlights the fact that not only did she serve as a judge, but she served as secretary of the Tennessee County Judges Association.

“In the language of the law, ‘the objection,’ entered by Mrs. Drake’s friends, ‘is sustained,’” the editorial ends.

The Nashville Banner editorial board was not the only entity that had to speak up for Judge Drake’s memory, though. In 1959, Judge Drake’s daughter, Jo Ellen, corrected the record via the Johnson City Press.

“A local woman has taken issue with an announcement last week by W.M. Leach, executive secretary of the Tennessee County Services Association, that Mrs. James B. Long, Decatur County is the first woman county judge in Tennessee history,” states the relevant article. “Mrs. William I. Vines, 1100 Barton St., said her mother, Mrs. Kate M. Drake, was the first woman county judge in the state and she has the records to back up her statement.”

Jo Ellen Vines’ intervention apparently led to a reversal.

“But last night, Leech [sic], reached at his home in Charlotte, Tenn., conceded his records may have been in error,” the article finishes.